Bishnu and I got up early to do housework, and then we left with Saano Didi and her kids for today’s rice harvest in her fields. Saano and Bishnu carried big baskets loaded with pots and array of cooking materials; I had a bucket of spinach in one hand, a pot of tea in the other (life can be so odd), and my audio recorder slung over my shoulder.

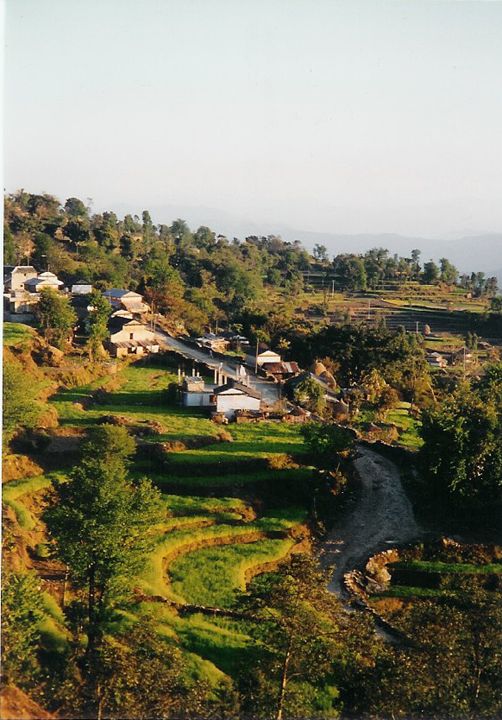

Saano’s boys and I stopped at the tap to wash the bucket of spinach. The ground still hasn’t dried out from the monsoon, and path through the rice paddies was narrow, slippery, and sometimes non existent. When we finally arrived, we found an elaborate and energetic rice thrashing, ox-circling, tea and rice cooking, straw flinging fiasco I am becoming familiar with. Mahendra’s father was perched on top of the hut-sized pile of cut rice stalks, smoking a cigratte and handing down bundles of crop every twenty seconds or so.

I ended up in the rice thrashing group. Our job is to pick up the bundles of cut rice stalks as Mahendra’s father unloaded them from the haystack. We lift the bundles over our heads and slam the grain end on a flat rock to separate out the seeds. Then we put the straw aside, where the straw flinging people shake it out and toss it over to where the are circling. Saano Didi’s son Kancha drives the oxen in circles and they trample the straw to soften it, so it is easier to carry (for us) and easier to eat (for our baby buffalo Sticky and her parents).

It’s quite a scene. Very spritely.

Today’s seen was mainly composed of boisterous men, slightly older than me and Bishnu, in their mid and late twenties. I make great entertainment, banging rice from the unreasonable height reached by my upended arms, hay sticking out of my hair and attaching itself to my lungi. Also, dudes in their mid and late twenties are just generally loud.

So for three hours while we thrashed and drove oxen and whatnot, we talked about America, our respective governments, poverty, wealth, opportunity, taboo subjects like royal murders. I was so glad I wasn’t logging tape in a carpeted sound studio.

Mean time, Saano didi was putting the pots and spinach and teapot to work over a fire she’d built nearby. When we had thrashed and trampled the entire haystack, we sat down right there in the fields to eat. Then I had to leave for school. While I was away they would have get all the grains into sacks and bundle the straw into loads, and spend the afternoon going back and forth carrying it all up to the house.

I returned late in the afternoon to see if there were more loads to carry. It had begun to rain, and the narrow, field-winding route was even more treacherous. I met up with the gang: Siete, a wiry young man about my age; Radju-daai, slightly older but youngish man, and Saano Didi’s husband, a solid ball of muscle a few inches and a few teeth shorter than I am.

I was a little surprised when Saano didi’s husband prepared for me to take over his enormous load, so that he could go get another. I’m used to everyone bending over backwards to find me the easiest work, and arguing to do more; this time, exhausted and wary of the path up, I was prepared to happily accept something a little easier. As they propped the fat white bag up on a ledge, someone asked if I’d rather take Siete’s load, which was a little smaller. Well, working off principle rather than common sense (and noting, after all, that nobody ever offers me harder work than I can do–I always argue my way in over my head), I shrugged and said I’d try this one.

Let me pause to explain the mechanics of carrying a 100 pound sack of rice on your head. One way to get started is to lift the heavy load from the ground. The bag sits there with a circular rope around it and you lean against it like a chair, stick your head in the sling, and as you lean forward you gradually take on more and more weight until you’re crouched beneath the sack. Then with a massive effort and a burst of leg power you stand up – that’s the hardest part, because you’re 100 pounds heavier.

Alternatively, the bag can be placed on a ledge, where you can sling it from a standing position and avoid the killer leg press. The tradeoff is that you don’t take on the gravity of the bag bit by bit using your muscles, either. Conveniently, it can be pushed right off the ledge. Onto you.

Today we decided to go with method number two. So I leaned against the sack, on a ledge behind me, slung the rope on my forehead, and crouched just slightly, to about 3/4 standing. I’d still have to pop myself up to full walking height, but it’s much harder from the ground and I already had a 120 degree angle in the knees. Raju dai moved the weight of the bag from the ledge to my back, neck, and 120 degree bent legs.

Go ahead and picture a perfectly balanced scale sitting next to a ledge. Now picture that a 50 kg sack of rice is ever so gently tipped off the ledge onto one side.

That’s me. One instant we are executing a delicate but routine operation; the next I am pinned to the ground by a sack of rice. It never passed go, it just went directly off the ledge and crashing to the ground with me underneath it. There no pause where my astonished quads considered staying at a 120 degree angle. There was never the slightest consideration of straightening up. Luckily, because I fell over on my side, my foot (the same one the ox tried to mangle a few days ago when I was a straw flinger) was the only thing besides my ego that got directly squashed. Of course, what with the enormous sack of rice on my foot (and my ego), I couldn’t get up. Or get my foot out. My excellent problem-solving skills eventually led me to remove my foot from my sandal.

Also, the sack of rice ripped. Thanks a lot, sack of rice.

With my first try now finished, I took Siete’s smaller load. He stayed behind to get a new bag for the one I’d ruined. Raju and I set off.

For the first bit of the climb, there was no path at all. We climbed up over the terraces, which are narrow and rocky, and by now it was raining and slick. Often getting up to the next terrace required a big step up, for which one would use hands and feet together even without the added body weight of a 100 pound sack of rice.

Not to worry! I gallantly wobbled and teetered my way up as awkwardly and pathetically as anyone has ever done in the history of rice cultivation. We came to a terrace that was about my height. Happily, I was able to pull myself up and over to the field above. Unhappily, I could not quite get the weight of the rice on my back to tip forward with me onto the upper ledge. So it did what a sack of rice does when it cannot tip forward onto a ledge. It tipped backwards off the ledge.

Given that said bag was slung to my forehead, this was rather terrifying, but luckily the rope slipped right off my brow. The traitorous bag went tumbling down, and I landed in an upside down hanging position with my legs on the ledge and my torso dangling off. A passer by (it’s a rather popular spot) might have thought me just shot by an arrow. Raju might have considered it.

Fortunately the sack was still in tact this time. I vehemently refused to let Raju carry it over the ledge for me, which I’m sure he found very thoughtful. We put the whole operation back together and set off again. By now my back was cramping and spasming despite the relatively easy load, and nobody needed to convince me not to go again when we reached Saano didi’s some untold hour later.

After getting over the initial shock of my actually having arrived alive, the tired crowd wasted no time rocking back on their stools and retelling tales of my performance over the course of the day. Everyone kept asking if I’d hurt myself, but other than my foot, I was fine–nothing had been badly bashed except my pride. Everyone’s attention was soon diverted to a vat of boiling millet alcohol. I have never enjoyed whiskey before, but it’s like they say when you’ve been twice attacked by a sack of rice: there is a time and a place for everything.