I woke up after our day in Lamjung feeling all grayed out. I didn’t want to get up so I stayed in bed until 8:45am, which is mid-afternoon here. Everything seemed complicated and shifty. I haven’t even been out to any of the real damage yet and I’m having trouble keeping my spirits up.

I went for a run along the lake in the hot sun, showered and sat down in a café with some iced coffee. I took out Manisha’s email from May 1 and reviewed it with everything in mind that I’ve learned now about transitional housing.

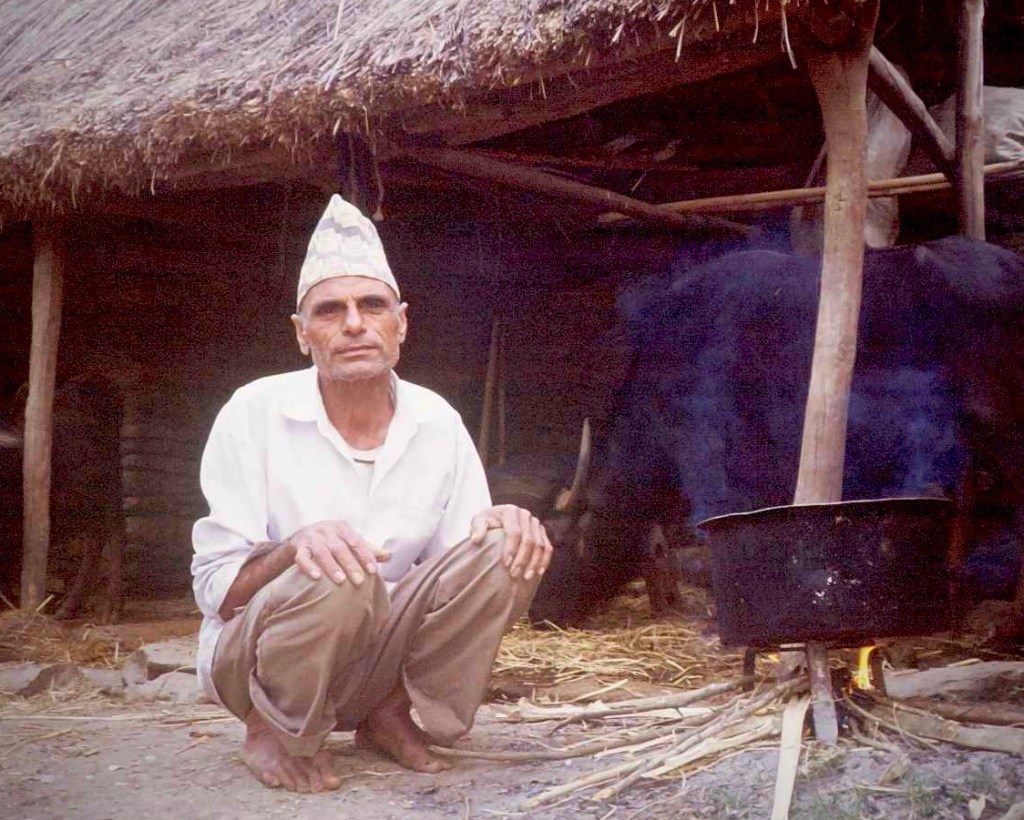

One thing that’s obvious is that there’s no more time for talking and thinking and researching without acting. We’re going to have to learn as we go. The basics are the basics – don’t impose ill-conceived ideas on people, focus on local resources and let people use their own knowledge to build. Supplement with structural ideas, manpower, and additional raw materials as possible when you know what can be used. Building for thousands of people at once in a short time is a different ballgame than designing the ideal temporary rural house.

I looked at how the destroyed and damaged houses are distributed among our working areas and put them in to an order I thought made sense for us to learn by doing. In some, where there are just 2-6 damaged houses, we can try something like earthbag building. In others, were there are 40 or 100 homeless families, we’ll follow the generally accepted plan to provide tin and manpower. We’ll see what happens and improve as we go.

I put this all in an email and sent it out to our advisory board. Things felt a little more organized. I needed to confirm that my data from our villages was still correct, because the second earthquake caused more damage, and also other groups may have already provided some materials to some of these places. But Kaski and Parbat, the districts where we are, weren’t hit as hard, so there’s a lot less attention here, even though hundreds of homes are unlivable. There are no big cluster meetings and the government is under very little public pressure to act quickly around here.

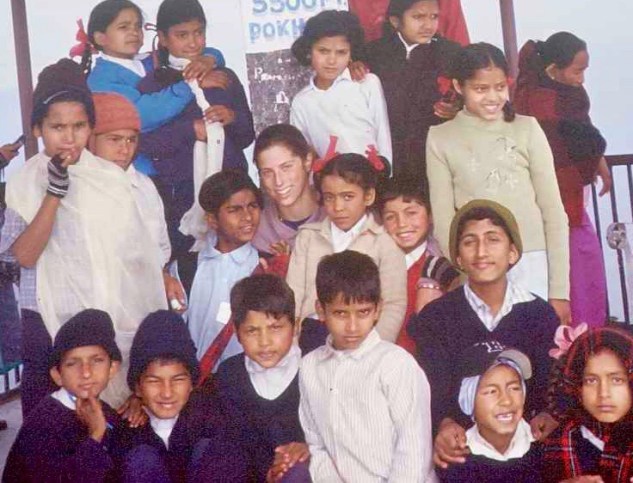

Once that was all sorted out, I headed to the Gaky’s Light community house. Our Fellows have the first performance of their final project tonight. It’s a tribute to earthquake victims that they’ve been working on with a dance teacher. When I arrived they were practicing and setting up a sound system outside. A crowd was beginning to gather around.

working on with a dance teacher. When I arrived they were practicing and setting up a sound system outside. A crowd was beginning to gather around.

As soon as the kids were about to start their performance, the clouds came in, purple and ominous. The rain began but they did their performance anyway, and people watched from under the eaves of shops on either side of the street. One man pulled over on his bicycle, wrapped up in plastic bags from head to toe. He was upset to find out that we weren’t collecting donations, which we weren’t allowed to do in a public space because there’s so much worry about people exploiting the situation to raise funds for dishonest purposes.

I decided to have dinner with the kids and sleep at the GL community house. Just as it was getting late, I got a message from Bene and Robin, French friends of mine who live in Pokhara, that there was a meeting the next morning in Sarangkot where they’d be doing presentations about earth bag building. So the next morning I got up and went straight to meet them in this crazy jeep they bought that looks like it was used for transporting goats or ammunition at some point.

Robin drives like a bat out of hell, and the road to Sarangkot – the same one I take many times each week to Kaski – isn’t exactly paved with pavement. I’m a pretty hearty passenger, but we were all in the back of the truck bouncing like popcorn, things rolling out the back, I hit my head on the bars a few times, all while trying to shout at the two other guys in the back of the jeep to figure out what we were all doing there. Then I was up at Sarangkot for a few hours with a random collection of foreigners who’d all been doing various forms of freelance aid, learning about how to build houses with earthbags.

This beautiful boy in the crowd started dancing during a tribute song written by our fellow Umesh, and kept going for a full five minutes.

For the record, I’d left the office at 2pm the prior afternoon, thinking I’d be back in 4 hours after watching a dance performance.

I didn’t get back from Sarangkot until late afternoon and went straight to watch the kids do their second performance. A good crowd gathered and lots of people were filming on their phones. But the instant their dance ended, the performance was once again interrupted by rain – this time a thunderous downpour of fat plops of rain and huge chunks of hail. We all ran under a nearby tin roof and waited it out while the sound guy pulled in all his equipment.

When the storm ended, most people had gone home. But the kids set up one of the speakers and did the rest of their show – a poem, a few more songs, and a candle lighting. It took all of them at the same time lighting and relighting the wet candles, hovering over them to keep them all going at once, to get the Nepal flag surrounded. And of course a new crowd formed around them.

My phone rang and I found out we had a last minute board meeting. I showed up quite wet and bedraggled at 6pm on the back of Shiva’s motorcycle. All my electronics were dead because I had no chargers with me. We ended up sitting there till the place closed, and I finally hopped in a cab and went home.

Well that’s kind of how things go here, moving from one universe to another on the backs of bikes and jeeps, following things as they unfold in the moment. I left the office at 2pm on a Tuesday thinking I was coming back for dinner, and didn’t come back until 9:30pm the next day, having been to up to Sarangkot in a jeep and hiked down through the woods for an hour and a half in my flip flops, watched two dance performances, run from hail, spent a night with the kids in the community house, and had a 3 hour board meeting while sipping an americano in a coffee shop under a thinly disguised knockoff Starbucks logo.

Nothing like a little Nepal style to shake you out of your gray and put you back on your toes…