It had been a long day for both of us: me at school, Aamaa cutting grass for the buffalo all afternoon in the heat. We convened in the kitchen as the sun was going down. Both of us were too tired to bother with rice, so Aamaa began putting wheat rotis in a pan for us to eat for dinner with some iskus left over from this morning. Iskus is my favorite vegetable, a slightly sweet gourd that’s plentiful at the end of summer. I was just about to bite in to a little scoop of it I had carefully placed on a nice hot roti, when shouting began outside.

It had been a long day for both of us: me at school, Aamaa cutting grass for the buffalo all afternoon in the heat. We convened in the kitchen as the sun was going down. Both of us were too tired to bother with rice, so Aamaa began putting wheat rotis in a pan for us to eat for dinner with some iskus left over from this morning. Iskus is my favorite vegetable, a slightly sweet gourd that’s plentiful at the end of summer. I was just about to bite in to a little scoop of it I had carefully placed on a nice hot roti, when shouting began outside.

So listen, my language skills are pretty good for someone who’s lived in Nepal for a total of a few months, but at the end of the day, I can no more decode haphazard shouting outside the door than I can follow a parliamentary debate. And since I can’t understand the words, it took me longer to notice the sound at all…and to be honest, I was really focused on my roti and my little pile of vegetables. So Aamaa was the first to jump up and run outside, leaving me in a momentary cognitive stall-out after a wearying day of trying to think in another language.

What about my roti? I thought, looking longingly at the little pile of carefully placed iskus. And then I snapped alive to the world outside, where my attention fully redirected to the ruckus coming through the door. Not wanting to miss any action, I put my down roti untouched, leapt up, and followed Aamaa outside.

It was dark and Aamaa had already taken off with the light. Our mountain alcove was thick with nighttime, but shouting was coming from all around, and leaping from squares of yellow light and vaulting off the terraces and bouncing maniacally about in the huge darkness.

I scrambled half-blind over the path from our house to the edge of the terrace, which drops off to the next field below. There, Aamaa stood at attention on the terrace edge, listening to the tempest of voices. Without warning, she let go an unbridled screech and submitted her own opinion to the fray.

There were no further clues as to what anyone was yelling about. I wanted to ask, but I was afraid to interrupt the flow.

Abruptly, Aamaa took off again. Now to the left, and down over the terrace, past where the buffalo stay in the winter; a patch of field that now, in late summer, is a wet leafy carpet. The Ritz Carleton for leeches. Determined to be a full participant, I ran after her, jumping over the terrace ledge, and plunging heedlessly through the soft plants to where she was standing with a flashlight, now yelling again. Two small girls had appeared out of literally nowhere; and logically, given the leech situation, they stayed perched on the ledge over my head.

“WHAT HAPPENED?” I asked Aamaa breathlessly, my feet absorbing moisture from the buzzing ground. I was rewarded with more incomprehensible shouting coming from everywhere.

Finally, without averting her gaze from the inscrutable darkness, Aamaa said something about a cucumber, which I couldn’t quite catch, except for “cucumber.” And then she was promptly too distracted to tell me any more.

I thought about the leeches. Fine. I returned to the base of the ledge, resolved to climb back up. While doing so, my sandal fell off. The two mystery girls wanted to to help me up, but on principle I fixed my sandal and got myself up the ledge. Still utterly baffled, I returned to our house with the two girls, and a minute later, Aamaa followed. The yelling wafted along behind us, still unattached to any source or story.

The girls had brought us what I now know was belaunti, a cheese-like, crumbly, slightly sweet milk product that comes from a buffalo that has just calved. It is packed with both nutrition and luck; birth, after all, is a dangerous and miraculous thing, and belaunti is treated with the respect any auspicious gift of the universe is due. But in that moment, all I knew was that we’d gone from the inexplicable cucumber crisis outside to an equally illogical and randomly-timed cottage cheese situation inside, which unfolded as follows: Aamaa put a bit on her forehead and then started eating it. Then she asked if I wanted some, so I said yes, and I was about to eat it when she told me to put some on my head first.

Alas, I’d started out tired, and my mental state was only becoming more fragile as the number of things that made no sense accumulated.

Just as I was trying to work out why the two mysterious girls had brought over cottage cheese while people were shouting about the cucumber, and why we had interrupted that serious event to put the cheese on our foreheads, Aamaa offered the girls some roti. I’d nearly forgotten about my once-important roti. And I forgot again, because in the half second it took the girls to refuse the roti, Aamaa had gone back outside to shout about the cucumber.

Not to be outwitted, I dashed back in to our yard, where now I found our neighbor Saano Didi and her three boys. They were standing as if squinting with their bodies, leaning slightly forward in to the darkness, watching the invisible shouting. I pleaded with Saano Didi to explain what in God’s name was going on. I just wanted to be in on the cucumber issue. I just wanted to play with everyone.

What followed was an extended five-way exchange that involved a fantastic amount of explaining and re-explaining, handwaving, pointing, and acting, in which I tried to piece together the story of the cucumber emergency based on comprehension of only one out of every fifteen words. At first I believed that somehow a cucumber plant had fallen over–I was not focused right then on the fact that our cucumber plant is most decidedly a vine–and I became very worried that somebody had been injured by a falling cucumber tree. But Saano Didi and her boys kept mentioning boys and girls; apparently the cucumber tree had fallen when too many boys and girls were climbing it, and a mystery man appeared–wait, no, the cucumbers were stolen! The tree fell over and the boys and girls were stealing all the cucumbers from it! Oh–no–a man came and stole all the cucumbers–but not from a tree, he went around to people’s homes and asked for cucumbers, and didn’t tell anyone else that he was exploiting cucumber generosity from them all–no, he didn’t ask, the man was just stealing cucumbers from each person’s house! And then he was CAUGHT! Ah, this was beginning to make sense–but wait, how did the man go running from house to house with a growing collection of cucumbers? Hold on, he was eating them as he collected them.

Yes, this surely explained the excitement! A man had been caught–well, seen, but escaped–while sneaking from house to house eating cucumbers. And now he had got away, despite the dazzling mountain-sized net of female screeching through which nobody could possibly run freely and un-apprehended, even without an untold number of cucumbers to carry.

Yes, this surely explained the excitement! A man had been caught–well, seen, but escaped–while sneaking from house to house eating cucumbers. And now he had got away, despite the dazzling mountain-sized net of female screeching through which nobody could possibly run freely and un-apprehended, even without an untold number of cucumbers to carry.

Saano Didi invited me over to her house. Aamaa was clearly indisposed with the cucumber crime, so I wasn’t to get any further intel any time soon, and I’d forgotten about my roti, so I went and sat by the fire in Saano Didi’s house and drank some hot buffalo milk. Then she produced a cucumber.

Which turned out to be the most enormous vegetable I’d ever laid eyes on. It could easily have crushed a cricket bat. It was of a stature that unequivocally qualified its seeds to be harvested for next year’s cucumber crop. This new evidence threw the cucumber fraud situation in to chaos all over again. It was hopeless. I would never solve it. Saano Didi cut the Gozillacumber in to massive, dripping hunks of flesh, and we sat slurping, crunching and dripping in cucumber juice, while somewhere unknown, some cucumber lover was apparently reclined in the dark recesses of his home, totally immobile.

*

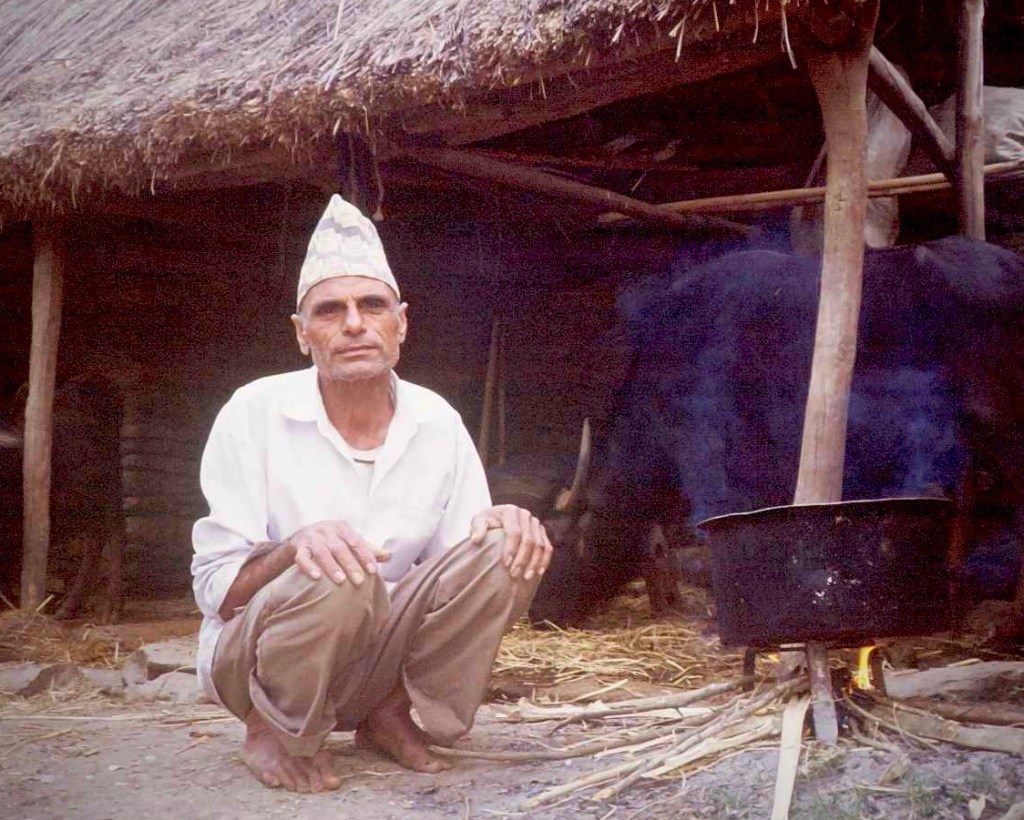

Aamaa with a Godzillacumber