Read this series here.

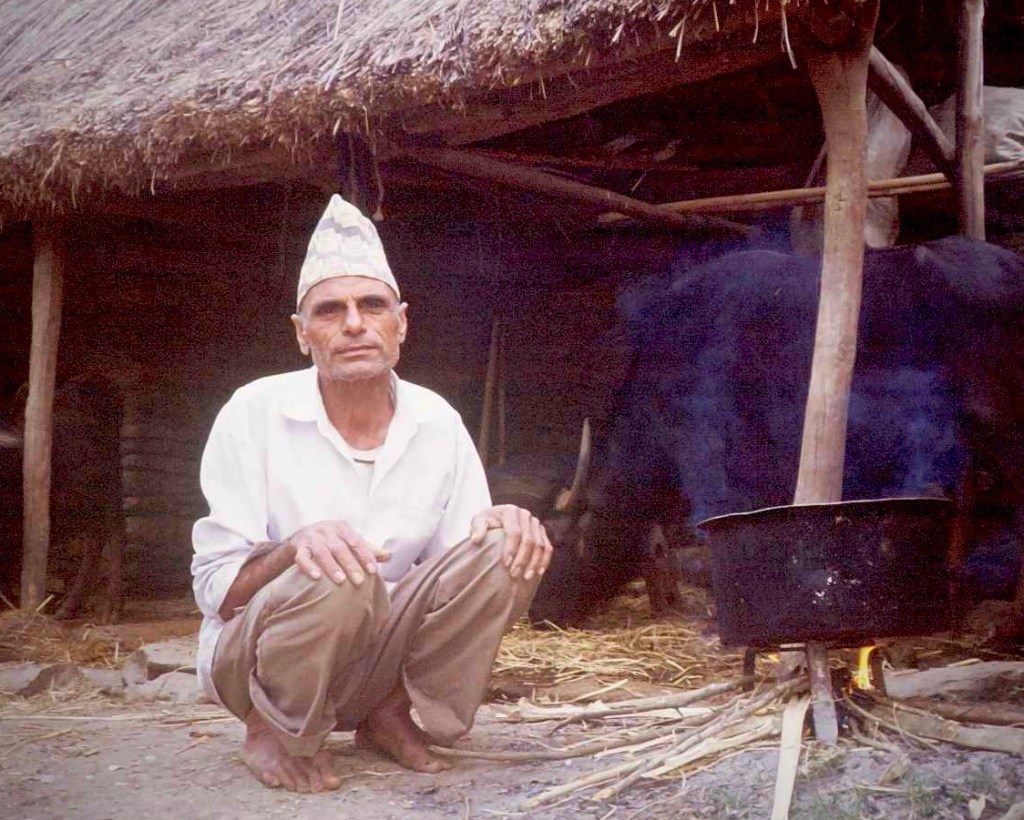

Over the years, I have witnessed many passages in Nepal. Marriages, coming of age ceremonies, births of animals and people, and deaths of many kinds. The weather itself has a careless drama about it, demanding reverence for the seasons and relentless passage of time…when it is hot, it’s time to plant millet; when there is a full moon, it’s time to fast; when a distant glacier becomes heavy, it’s time for it to break apart, time for the river it lands in to overflow in a torrent, time for an entire village to be swept away. When it is morning, it’s time to get up and cook breakfast.

Over the years, I have witnessed many passages in Nepal. Marriages, coming of age ceremonies, births of animals and people, and deaths of many kinds. The weather itself has a careless drama about it, demanding reverence for the seasons and relentless passage of time…when it is hot, it’s time to plant millet; when there is a full moon, it’s time to fast; when a distant glacier becomes heavy, it’s time for it to break apart, time for the river it lands in to overflow in a torrent, time for an entire village to be swept away. When it is morning, it’s time to get up and cook breakfast.

The intimate relationship between people and cycles in this part of the world is one of its most moving qualities. I think it is a hard thing to see if you have always been inside it. But I am outside of it. And peering in, I am endlessly preoccupied with how a single human existence can be subtly accepted as a grand and meaningless expression of a larger constellation of forces and relations and nature, awesome because it is small, not because it is unique. I only notice this because I learned to see myself as separate from the moment I came in to the world. In the West we gain power, intelligence and purpose from our individuality. But it’s something I can’t explain to Aamaa. There simply isn’t a vocabulary to say that my life possesses a greater idea than the idea of the universe itself.

I know I’ll never be comfortable with this fact. Instead, I am perpetually drawn to these rites of passage, which integrate our small lives with those of our ancestors, with the cosmos, with God and with the future. Perhaps it’s like continually trickling cool water into a wound that will always burn.

This winter I’ve decided to start a project that has been some time in the making. Since I first began coming to Nepal in 2002, young men have flooded out of the country for migrant labor in gulf countries; last year, over 300,000 people left for that purpose alone. A surprisingly large number of these young men die abroad, and when they do, normal mourning rituals are turned completely upside-down. Many of the essential features of customary mourning become impossible. My project will document the way that families have adapted ritual grieving when their sons die overseas.

Nepal’s funerary customs in the weeks that immediately follow a death are called kriya. There is great intelligence and beauty in these rituals, which provide a structured role for the community and extended family in sharing grief, reaffirming ties, and placing the life and death of the deceased in to a coherent cosmic story. Many aspects of kriya are austere and demanding, putting physical and mental purification above comfort, and imposing isolation as a sanctuary for the emptiness that follows loss. When the kriya period ends, other rituals last weeks, years, and in some cases, forever. Aamaa, a widow since age 23, hasn’t worn red in 35 years. Anyone who meets her can immediately know without a word that she is widowed – if they are attuned to this custom.

Stories of grief and loss in other places have immense importance for us. Ritual grieving in American culture is increasingly short-lived and mainly the private domain of the bereaved. Death as a matter of politics or policy or violence is in our media every day. But mourning, the outward expressions by which we integrate death in to the un-ended lives of the living, seems to be on the periphery of our inquiry, at best. In some ways, mourning is treated as an obstacle to our collective concern with affirming and carrying out our individual significance.

But mourning is a choice we make to ascribe meaning to our grief. It is a willful sanctification of our mortality. We hope for the grace to extract from this some kind of redemption, something beautiful about life. Or perhaps simply the courage to keep living.

In the course of this series, I hope to honor the beauty of Nepal’s kriya traditions, as well as a generation of young people caught in the ambiguous place between a world that has shattered and one that does not yet exist—at the threshold, in that empty uncertainty, where we are reinvented.

. . .