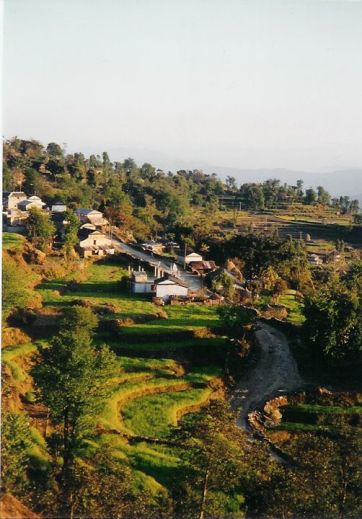

It was nighttime as we flew in yesterday, so I couldn’t watch the terraced hills coming in closer and giving way to Kathmandu’s gritty buildings. Staring at the city lights flickering in the vast darkness below, I felt a wave of sadness. I couldn’t shake the feeling of arriving in a foreign land and it made me feel like a foreigner to myself.

The normally quiet tarmac at the airport was scattered with a handful of helicopters and few gigantic cargo planes with their hatches open. And in a way that only Nepal can do, it seemed that someone had made an effort to spruce up the airport for an onslaught of international visitors: a new routing through the arrival area, which wound past a recently installed station where a vinyl banner reading HEALTH DESK had been mounted. A large sign announced that anyone having recently come from Africa was required to stop at the Health Desk for processing, and behind it, an airport official was tinkering with his iPhone. We all shuffled past him, to the main arrival terminal, where the computers weren’t working.

I was one of only about five foreigners waiting for a visa, which was new. And the baggage scanner that was previously set up at the airport exit was gone, probably to make way for a more official exit procedure. But to either side of the revised exit procedure were piles and piles of packages. I took a photo of a stack of boxes addressed to a hospital; it did not look anyone was in much of a hurry to get these parcels distributed.

I was one of only about five foreigners waiting for a visa, which was new. And the baggage scanner that was previously set up at the airport exit was gone, probably to make way for a more official exit procedure. But to either side of the revised exit procedure were piles and piles of packages. I took a photo of a stack of boxes addressed to a hospital; it did not look anyone was in much of a hurry to get these parcels distributed.

Following Tuesday’s second earthquake, everyone is taking precautions again. On the cab ride from the airport, I didn’t see many damaged buildings, but people everywhere had tents up outside along the road. I stayed with a friend and the whole family slept on mattresses in the living room, right by the front door, which was left unlatched. That’s where we are again tonight.

Today I spent the day getting a taste of local relief efforts, and it validated my early suspicion that the energy and creativity of locals can’t be dismissed. My friend Dr. Kiran Awasthi, who has trained all our dental technicians through his organization, has been furiously working with a group of high school classmates to distribute sanitation materials that will help prevent disease outbreaks. His connections through the private sector and health ministry have allowed his group to become a trustworthy distributor of hard-to-find supplies. They’ve also researched, designed and built a temporary housing unit in just two weeks, and they’ve tried it out in some areas already. Obviously the government will ultimately have to take the lead on a large scale, but groups like this are doing a huge amount to help get there more quickly.

Today I spent the day getting a taste of local relief efforts, and it validated my early suspicion that the energy and creativity of locals can’t be dismissed. My friend Dr. Kiran Awasthi, who has trained all our dental technicians through his organization, has been furiously working with a group of high school classmates to distribute sanitation materials that will help prevent disease outbreaks. His connections through the private sector and health ministry have allowed his group to become a trustworthy distributor of hard-to-find supplies. They’ve also researched, designed and built a temporary housing unit in just two weeks, and they’ve tried it out in some areas already. Obviously the government will ultimately have to take the lead on a large scale, but groups like this are doing a huge amount to help get there more quickly.

My second stop was with a group called Women for Human Rights. Before the earthquake, I had planned to visit them on this trip to do an interview for a radio story I am producing about young widows in Nepal (as part of a series on migrant labor called Between Worlds…but that’s another story!). Like everyone, Women for Human Rights is also doing what they can towards relief, in this case for women especially. So I interviewed their founder about their aid efforts, and then went to a shelter they’ve set up for young mothers and children. It is a large canopy at one of the tent cities in Narayanchaur, at the center of a gigantic grassy mound in the middle of a traffic circle. I interviewed a 22 year old girl whose baby was three weeks old when the earthquake struck. When I asked the kids what they thought of spending their days lounging and playing in the hot sun at the camp, a twelve year old girl chirped: “It’s fun!”

I know that the government and army are making major efforts, and personally I believe very strongly that the government should be viewed with high expectations, tasked with responsibility, and held accountable. But that said, there is huge distrust among the people of Nepal and the international community about the government’s ability to distribute aid, much less rebuilding, quickly or equitably. There are still swaths of the hillsides where people have lost everything, suffered injuries and death, and received NO AID. I couldn’t help noticing that when I walked past the police station, about two dozen officers were hard at work breaking, organizing and laying bricks – rebuilding the wall of their own compound.

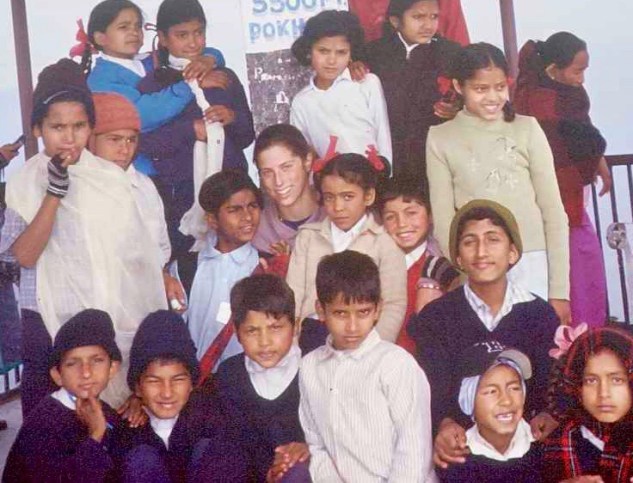

So that was a pretty long day. I already have hours of tape to sort through and tomorrow will bring a whole new chapter of stories before I fly to Pokhara at 3:00. I’ll be glad to get out of Kathmandu – about 70,000 people have left the city since the second earthquake on Tuesday.

Nepal has always shown me a graceful, practical relationship with nature and its whims. But everything feels wrong. Twice today I was in the middle of a conversation with someone who suddenly stopped and said, “Is that an aftershock?” and I couldn’t even feel any shaking. Everyone is on a razor’s edge. People keep telling me, “Things were getting back to normal,” when talking about the second earthquake, which really tells you something, because things were definitely not normal last Tuesday morning. But the second time seems to have redefined “not normal.” It’s as if now the injury of this event is not yet quantified – the sensation isn’t that something terrible happened, but that it is happening, and the final damage is unknown. As long as the cost remains pending, the reckoning is impossible. You can’t mourn much less rebuild something that is still breaking apart. Everyone is just waiting, even as they run around providing aid to each other.

I will be glad to get to Pokhara tomorrow, but I think this month is going to be as strange and unsettling as expected. My mind is racing with ideas for how to make the best possible use of the $14,000+ we raised for aid, and it is good know that we have the ability to do something, or to provide significant support to someone doing something effective and under-funded. One idea I’m thinking about is collaborating with Kiran or a similar group working on temporary housing. Tomorrow, I am going to get an overview of how the big aid is working.

But I will write about that tomorrow!