We spent a very long time waiting for the milk truck to pick us up. As part of Optional Class, I’ve found people to come up from the city and tell the kids about their jobs: a librarian, a radio jokey, and someone from the photo shop. Today, we were headed to Pokhara to visit the places they work.

While we waited for our ride, the kids sat on the grass, leaning on each other, practicing the song that Govinda and I wrote about the solar system. We make them sing it every day – Venus has poisonous air, there’s a big storm on Jupiter, la la – so the tune has more or less become the Optional Class Anthem. The radio jockey had invited our students to sing the solar system song on air during our visit, and the quartet selected for that job was practicing next to a few other students who we’d chosen to read their poetry on the radio. The early morning hour was one of quiet satisfaction for Govinda and me, watching our kids with their heads bent over the books they’ve made, feeling important.

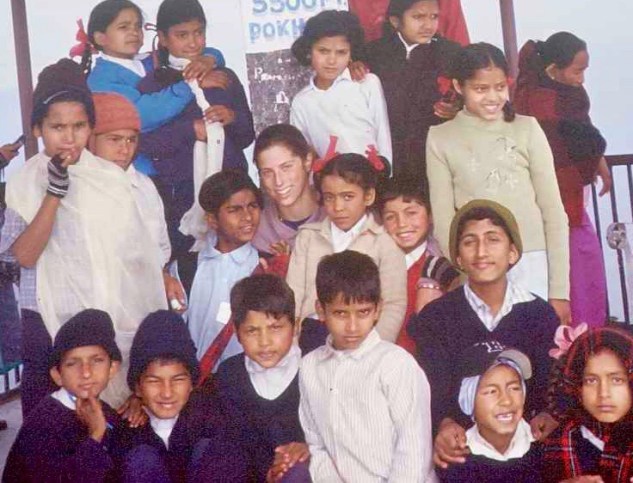

The milk truck finally came, and we all crammed in to the back: Govinda, Laximi, and eighteen kids, and me. The inside was a military-style canvas box with two benches and railings on the ceiling to provide handholds. With a lurch we set off, bouncing down the dirt road toward the city.

The inside was a military-style canvas box with two benches and railings on the ceiling to provide handholds. With a lurch we set off, bouncing down the dirt road toward the city.

To keep out the dust from the road, we had all the canvas flaps down over the back and side windows. I looked around at all the little faces squashed into our sealed box, and was struck with the sudden feeling that nothing, no words or photos or documentaries, would ever be able to recreate that stuffed space. At the end of the day, we will be exactly that: a giggling ring of faces pressed together inside our container, moving along a dirt road towards something, out into a world which sees us as if from above, tiny on the crumpled earth. The instant reels in my mind from its birds eye view, and I look from the inside out, where we are now, and fall on the moment with a surrendering crush of love.

Because the outside is moving, moving, always crawling along the road, but the inside—the inside is still, aside from the bouncing. With the windows covered we couldn’t see the road going by, or the place we’d come from, or where we were headed. And when I considered that we would eventually arrive, and get out, and be outside too, I felt the weight of a universe crammed into a milk truck. This is our now: the gravity of all the past and future collapsed into a present that will pass and forever be gone. It seems almost impossible, amazing, to be here now. In a milk truck, with these kids.

*