Back in Kathmandu, Tom and Jerry ends, and we turn off the television. We eat our rice. I mush the grains between my fingers but resist the temptation to try to give the meal special attention. You can’t grasp a thing at the last minute if you weren’t paying attention along the way.

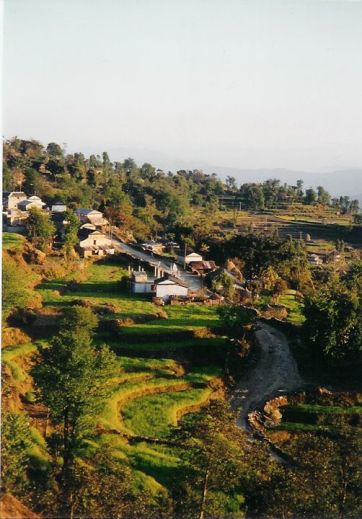

I repack my bags, and don’t get in bed till after midnight. With the heat and mosquitoes it’s a long time before I fall asleep. I toss and turn, thinking about watching Bishnu and Bhinaju get in the bus back to Pokhara, and about the strange idea of being even farther away than I am now. It seems like, for the rest of my life, I will keep getting farther and farther away. Which is strange because, even from Kathmandu, in a big bedroom where I can hear Nepali music videos playing on TV, Kaskikot feels like a memory, a separate universe where I once was. I was there only a few days ago.

You know, it never has been missing it that I dread, or the thought of loneliness that fills me with worry. It’s the shift from real to remembered, from substance to recall; it’s that the absence has no bulk when you get far enough away, and that life goes on and—even if you can remember to miss it, it’s so disconnected, so unreal, that it’s mostly just a story. And what of the part of you that has become the story, the skin that has touched this world and walked on it and dug fingernails into its mud? When all of it is farther away than the moon—which at least your eyeballs can see at night—is that part of you just a story, too, that only exists to the extent that you still believe you were there?

Wouldn’t that be something, if after all this, all I could bring home with me was a story.

*