After my visit to Bharte, I went up to Besisahar to spend the night. Many of the international NGOs working in Lamjung operate out of a hotel called the Himalaya Gateway, and I wanted to sit in on a training by the Danish Red Cross on shelter distribution. Plus, I had to retrieve our first delivery of tin: two bundles for Uttam’s family.

I arrived bedraggled and hungry at the hotel at 8:15 pm after many hours of hiking up and down in Bharte in my flip flops (points for irony on the hotel name, Himalaya Gateway). I sat down and talked for a while with Laurienne, the head of CARE’s relief effort in Lamjung. I’d met her at one of the shelter cluster meetings and found her to be a really nice person, so I’ve kept in touch. It’s pretty funny that I’m running around in my flip flops in Bharte and taking a bus to Besisahar to a pick up our first two bundles of tin, while Laurienne is coordinating the transport of 1200 bundles of tin on 28 tractors – TWENTY EIGHT TRACTORS – we had a good laugh over just the image of 28 tractors climbing up the narrow jeep “roads” of Lamjung district. A bit of a nervous laugh, too. The delivery of all this tin is probably going to take a toll on Nepal’s fragile environment. The Red Cross has committed to almost four times that many homes in Lamjung alone – one of the less affected districts.

Speaking of damage, I got myself a pint of ice cream (“Ma’am, how many scoops would you like?…The whole container?…????…Certainly.”). I turned on the air conditioning in my hotel room which noisily and enthusiastically set to delivering air at the same temperature as the rest of the room. I took a shower and fell asleep on the fluffy bed.

The next morning I went to the Red Cross shelter training. It was super interesting, but probably not something I will be able to use much. The topic was how to conduct efficient mass distribution of tin sheets, building kits, and envelopes of cash. For your kind information, and so I can make some use of my training, I offer you the following tips on distributing thousands of corrugated tin sheets to remote Nepal: distribution area has one entry and one exit; recipients move through in a single straight line only, no criss-crossing; vests must be worn at all times and a flag clearly visible to signal that this is a humanitarian space; a question and complaint-receiver stays outside the delivery area.

Also, it is suggested that your team (and, one assumes, your tractors) arrive at your distribution area the night before. Because there might be some problems with travel. Maybe.

Mean time, I was coordinating our first delivery of a grand total of two bundles of tin for Archalbot. In the morning, I ran in to the Chief District Officer of Lamjung at the hotel, and of course, we are old friends. I said I was delivering two bundles of tin today in Archalbot and asked if he had any transport suggestions.

The Chief District Officer looked at me funny and said, “Two?” Awkward pause. “That…doesn’t seem like a enough.”

Right right, I said. True enough. But see it’s part of this thing that’s going step by step. I promised there’d be more. There will totally be more. Also, I’m two bundles ahead of the Red Cross, and I’m going to enjoy every bundle of my lead for each hour that it lasts.

It was about 2:00 by the time I hopped in to a truck with our two bundles of tin. The hardware store owner had a delivery vehicle that was headed south anyway, and agreed to take our tin sheets (and me) for free. And thank goodness this truck was large enough to house a killer whale, because only thing inside it was our two little bundles of tin, which you literally couldn’t even see in the gaping darkness.

We hit the road and I called Kripa to say I was on my way with Uttam’s roof.

When we arrived in Bote Orar to unload the tin by the side of the road, about eight people from Archalbot had come down to roll the sheets and carry them up to the village (note to self: get a tractor when it’s time to deliver tin to the other 15 families). I hoisted an end of one tin roll over my shoulder, uttam’s sister in law took the other, and we were off.

When we arrived in Bote Orar to unload the tin by the side of the road, about eight people from Archalbot had come down to roll the sheets and carry them up to the village (note to self: get a tractor when it’s time to deliver tin to the other 15 families). I hoisted an end of one tin roll over my shoulder, uttam’s sister in law took the other, and we were off.

I could hardly believe it when I arrived at Uttam’s house. I’d only been away for 24 hours, but what used to be the tarp shelter in one field was now two bamboo frames under construction, with lots of people about.

The family called me for snacks. They had gone to buy a few kilograms of meat – a pricey indulgence – to feed to all the people.

Later, I was talking with Uttam’s brother. Even after all the days we’d been in Archalbot, working on the earth bag house, sleeping in Kripa’s home, stopping by to visit people in their yards and encouraging them to go cut bamboo, eating and bathing and washing our clothes with everyone else – after all this, Uttam’s family wasn’t completely convinced that we’d really show up with their tin.

It wasn’t until I’d called from the truck a few hours earlier, to say I was on my way from Besisahar with the tin, that the mood turned celebratory. That’s when someone was sent out to buy the meat.

Oh, and also, added Uttam’s brother, they’d made this excellent and spacious bamboo frame, and as I could plainly see, one bundle of tin wasn’t going to be enough to cover it. They would need another, he informed me.

Very clever, Uttam’s brother.

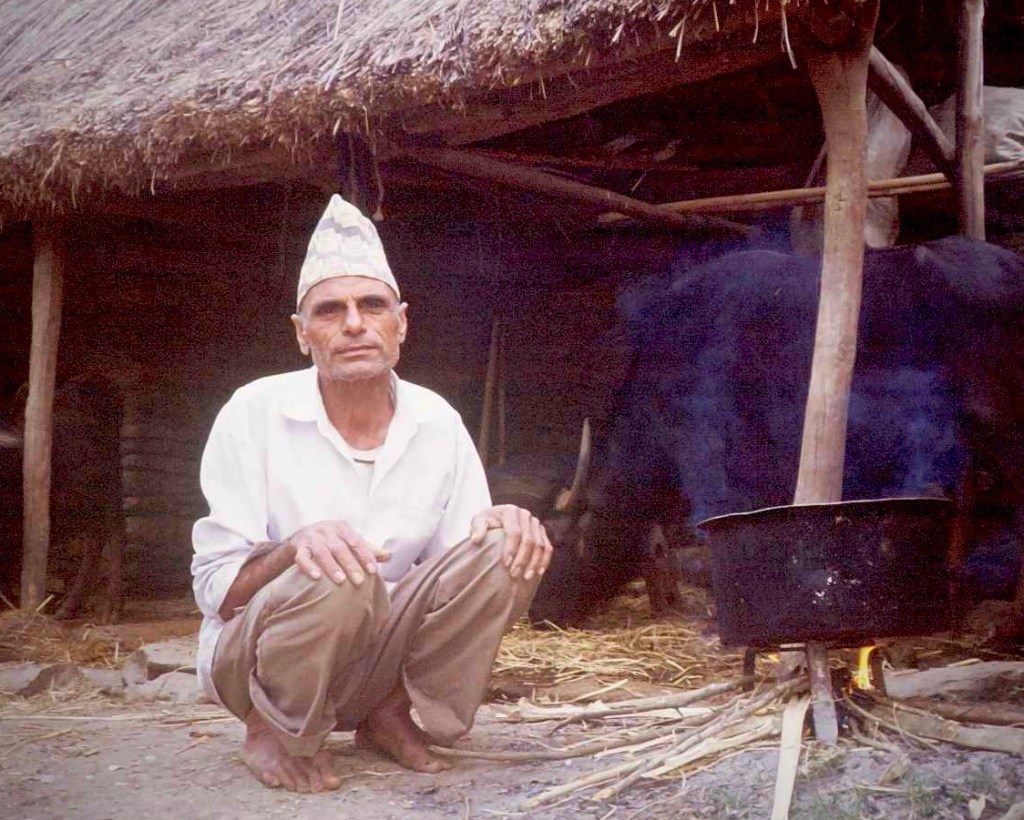

If there’s one moment that will stay with me the most, it’s when I asked Uttam’s oldest brother, who is building the  smaller upper house, to explain what each area of the inside would be when it was done. He and his wife had clearly thought about this. He pointed to the place where the kitchen fire would be, and the sleeping area (there weren’t exactly a lot of rooms, but that’s not the point). I motioned to a spot at the edge of the house that was a few feet wide. From the frame it was clear that the roof would slope down over it.

smaller upper house, to explain what each area of the inside would be when it was done. He and his wife had clearly thought about this. He pointed to the place where the kitchen fire would be, and the sleeping area (there weren’t exactly a lot of rooms, but that’s not the point). I motioned to a spot at the edge of the house that was a few feet wide. From the frame it was clear that the roof would slope down over it.

“What is this for?” I asked.

“That’s a place to stay if someone comes to visit,” he said.

Uttam’s family’s two houses are still going up, but before I left the next morning, I was happy to take this picture of his wife and two month old baby. Another small bundle in a big space…nice improvement.

. . .

I’ve been here three and a half weeks and I haven’t spent a single day in Kaski. Wednesday is millet planting day, so I promised Aamaa that I would take a day off from coordinating housing outreach and tooth brushing programs to come churn up dirt between the corn stalks and shove little millet seedlings in to it. I spent the rest of Tuesday running around, planning for a day in Kaskikot away from internet like it was year on Mars. Finally I ran to the bus park at 5:30pm, just as a downpour began.

I’ve been here three and a half weeks and I haven’t spent a single day in Kaski. Wednesday is millet planting day, so I promised Aamaa that I would take a day off from coordinating housing outreach and tooth brushing programs to come churn up dirt between the corn stalks and shove little millet seedlings in to it. I spent the rest of Tuesday running around, planning for a day in Kaskikot away from internet like it was year on Mars. Finally I ran to the bus park at 5:30pm, just as a downpour began.

For one thing, “Laura” is, exactly, the Nepali word for “stick.” This is an endlessly entertaining point. I look like a stick and I’m carrying sticks and my name means stick. Unfortunately for me there is also a lot of discussion about actual sticks (after all we are in the forest chopping wood) and I am constantly answering “Yes?” in response to people saying things like, “Hey, give me that stick.”

For one thing, “Laura” is, exactly, the Nepali word for “stick.” This is an endlessly entertaining point. I look like a stick and I’m carrying sticks and my name means stick. Unfortunately for me there is also a lot of discussion about actual sticks (after all we are in the forest chopping wood) and I am constantly answering “Yes?” in response to people saying things like, “Hey, give me that stick.”