My first solar eclipse was in sixth grade. Our science teacher, Max – I went to a progressive school where we called our teachers by their first names, so I actually had a real science teacher named Max – took us outside and we sat in the grass, next to a blacktop, near the soccer fields. In groups, we held something up in the air and peered through it, a notecard with a hole in it, or something like that. I don’t recall exactly. The entire memory is just an image of us, kids, sitting by the blacktop, holding a thing up in the air and squinting. I found it rather tedious.

My first solar eclipse was in sixth grade. Our science teacher, Max – I went to a progressive school where we called our teachers by their first names, so I actually had a real science teacher named Max – took us outside and we sat in the grass, next to a blacktop, near the soccer fields. In groups, we held something up in the air and peered through it, a notecard with a hole in it, or something like that. I don’t recall exactly. The entire memory is just an image of us, kids, sitting by the blacktop, holding a thing up in the air and squinting. I found it rather tedious.

My second solar eclipse fell on the festival of Maghe Sakranti. Before the solar eclipse, there had been a number of times when Maghe Sakranti had coincided with the day of my departure from Nepal, so over time, during visits when I found myself still there for this festival, Maghe Sakranti and its associated rituals had taken on a special flavor of celebration. We were still together.

In the days leading up to the eclipse, I was at school from early in the morning right up until dusk, painting. Govinda and the kids and I were rushing to finish a mural before yet another departure. It was a picture of their community: haystacks and houses, the whipped-cream shaped Kalika Hill with its little temple at the top, a paraglider sailing overhead, and road winding around from one place to the next, with a dominating school at the center.

As the day of the eclipse approached, there was a great deal of anticipation. Everyone was talking about it. Once, Aamaa said, she’d been out during a solar eclipse and, just like that, it had turned to night. They’d been forced to wait for a few hours until it got light again so they could go home.

Now that was something I wanted to see.

I went to visit Thakur sir, the astrologer, to get his opinion on a gift. Back home, a great healer and teacher of mine was losing her eyesight. I had purchased a necklace with the symbol kali chakra on it, and I wanted to ask about taking it up to the temple to be blessed, or infused, or something of that sort. I wasn’t exactly sure, but I thought Thakur sir would know what I meant to ask. A solar eclipse, he said, would be a very auspicious day to bless a necklace, even though it wasn’t allowed to do a puja during the hours of the eclipse itself. And, once the necklace was up there at the temple, at the top of the Kalika hill, I couldn’t take it away until the eclipse was over.

The movement of necklaces was one of many things couldn’t happen during the eclipse. Everyone would fast, of course, from exactly 12:36pm to 3:30pm, and many people would fast the whole day. Any water in the house would have to be poured out after it was over, and replaced with fresh water from the tap. It is wood cutting season, and trips to the forest were put on hold for the day. And Maghe Sakranti was, for all intents and purposes, cancelled.

In the U.S., a solar eclipse is, for the majority of busy people, a science project for kids. But here, where astrological charts are consulted for even the opening of businesses and choosing of brides, everything seemed to slow down as the days spiraled towards a grand and humbling halt. Gazing at the top of the Kalika hill against the sky, I could feel the world catapulting through the solar system to a particular magical position—a great thing getting closer and closer to us, small people, standing where we would witness the movements of the galaxy.

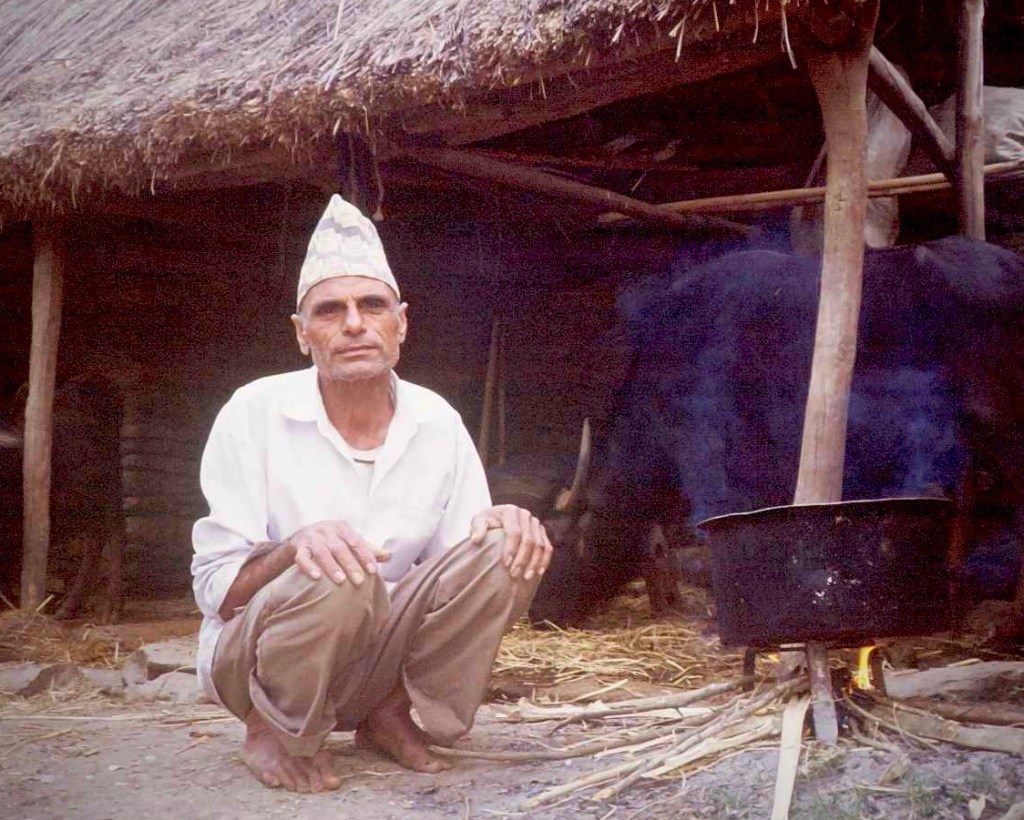

By the prior night, there were three buses waiting to take people all the way to Chitwan in the morning so they could bathe at the place where the Trishuli, Gandaki and Kali rivers meet. First thing in the morning, Aamaa repainted the floors with a fresh layer of mud. It would be a day filled with ritual.

Like the rest of the world, I had hoped to stay put for the solar eclipse…but the mural wasn’t finished. We had painted and painted that week, trying to finish in time, but when we pounded the lids in to the tops of the metal paint canisters the night before what should have been Maghe Sakranti, our creation still wasn’t complete. So I departed for school early in the morning, swearing to Aamaa I’d be back by noon so that I could eat before the fast.

I met Govinda in the road with the necklace in my pocket. When I’d taken it out that morning, I’d been surprised to see how mysterious and powerful the kali chakra looked, separated now from the rows of silver and symbols in the glass case at the shop. When we passed Thakur sir’s house, I put it in his hand and he gave it a long look. I wasn’t sure if I’d actually end up giving it to my teacher back home. I thought I’d send it up to the temple during the solar eclipse, and then give it away later if it seemed appropriate. I was afraid it might seem kind of silly, and ridiculously enough, decided I would ask the priest at the temple for an opinion when I went to retrieve it later; after the solar eclipse.

Govinda and I arrived at school to find the kids waiting anxiously, and out came the paint. I had stayed out past the witching hour, painting a mural, many times over my years in Kaskikot. But there was no thought of that today, not in the quivering air, under the glare of that acute collective focus on the cosmos. I was incredibly  excited. It felt huge and magical and a little ominous, and made me think about what it must have been like for ancient cultures that didn’t know the science behind such events. It must have been incredulous and awful to see the sun – so reliable! – disappear in the middle of the day!

excited. It felt huge and magical and a little ominous, and made me think about what it must have been like for ancient cultures that didn’t know the science behind such events. It must have been incredulous and awful to see the sun – so reliable! – disappear in the middle of the day!

And that’s how we found ourselves rushing to complete our masterpiece before the stroke of noon, small people painting small people, the sun under the brush racing the sun circling in the sky. “The eclipse is coming!” passers-by admonished us. What were we doing out?

At 11:15, we decided we were done, and with terrible haste threw remaining paint in to boxes, picked up old gloves, ran and locked the office, forgot something in the office (Unlock the office! The eclipse is coming!) and, at last, set off running down the road to get home before the eclipse struck us dead in the road. Kids peeled off at their homes. As we raced by in the dust, people called to us from their houses: Hurry! The eclipse is coming! There had been conjecture that we would see stars. The entire world was about to evaporate.

I made it home by noon, in time to eat. One o’clock in the afternoon, twenty-four minutes after the official start of the eclipse, brought a subtle change in the quality of the light.

Bhinaju and Bishnu and I decided we would climb up the hill behind the house and watch from the resort. We set to discussing what we should bring along. A flashlight? Poncho? Extra sweater? Rubber bands? Camera? (Would it be too dark for photos?) We rummaged around and put some belongings together. We climbed up to the top of the hill. And there I was, surrounded by a Himalayan panorama during a solar eclipse! I wondered if I would be permanently altered, perhaps suffused with some kind of wisdom?

We sat in the grass. We waited.

We stared earnestly at the sun for 30 minutes before admitting that we could see nothing.

We came home and sat on the porch. It was a devastating disappointment. I took out my journal. I became impatient for tea. As I looked a the water vessels and thought sullenly that we’d have to fetch new water before we could make tea, I considered the idea of “touched” water – that’s the word, chueko, “touched” water, the same word used for the impurity that a menstruating woman imparts to the things she contacts – and it occurred to me that all of these rituals – abstaining from pujas, fasting, dumping touched water – were fundamentally based in a fear of the awesome, not a celebration of it. Too bad I wouldn’t see anything. Even Maghe Sakranti had been cancelled.

For some reason, some of Aamaa’s old, beat-up x-rays were lying in a large envelope on the porch. I have no idea why. She’d had them taken when she was first sick, eight years ago; one of the slides showed her ribs and abdomen, a faded spine in the background, and another, a ball and socket joint. Maybe they’d been deposited in this random location during a recent tidying, or while we’d been arranging articles to bring on our failed observation mission an hour earlier.

I was writing when Bhinaju suddenly said, “Laura, come here.” He was standing in the yard, holding up the ribs and studying them. I thought he wanted to continue a recent debate we’d had about the number of vertebrae in the spine.

“Why,” I mumbled. “Vertebrae?” I was in no mood to be proved wrong.

“Just come here.” He switched to the ball and socket.

I got up and went to stand beside him. And right there in Aamaa’s humeral head was a clean outline of the sun with a smooth bite out of the upper left-hand corner.

For the last twenty minutes of the solar eclipse, as the bite of shadow moved eastward and the sun became whole again, Bishnu and Bhinaju and I leaned together, small people, holding the x-ray over our heads and squinting. We exclaimed and pointed and cried to each other: “The x-ray! The x-ray! It was here the entire time! If we’d had it on the hill, what would we have seen? What??”

–

A tarp has been put up a respectable distance away from the water tap, and we set everything down. Just on the other side of the spring there is a sizeable concrete shelter for kriya mourners that was built with funds raised from the community. This gives you an idea of the deference paid to these customs.

A tarp has been put up a respectable distance away from the water tap, and we set everything down. Just on the other side of the spring there is a sizeable concrete shelter for kriya mourners that was built with funds raised from the community. This gives you an idea of the deference paid to these customs.