There’s nothing like my first visit to Kaskikot after having recently arrived in Nepal. Granted, sometimes there’s a year in between visits, and in this case I was here just last summer after a long winter stay. But still – today did not disappoint.

I woke up to the charming experience of Pascal throwing his arm on my head. Let’s face it: this room where Didi and Bhinaju live is too small for all of us now, but we are persevering while the house is being built. It is the nights when I share a bed with Aidan and Pascal that I question my judgment in teaching them taekwondo while they are awake.

While Didi made tea, we all lay in bed debating whose fault it was that we’d all spent the night practicing kickball rather than sleeping. Then we documented our morning in selfies.

Late morning, I met up with some of our graduated Gaky’s Light Fellows for lunch. It was so great to see everyone and hear what they are doing. Sandip is marketing for an online news outlet. Ramesh is deciding where to apply for his bachelor’s in journalism. Nirajan is in Kathmandu, working for Teach for Nepal, and Nischal is entering his second year of bachelor’s. Umesh and Narayan have a solid paid gig singing traditional music each night, and Narayan has his own radio show. Bhagwan is a residential supervisor in a school hostel. When Puja and Asmita finally got there a few hours late, we all made plans to go boating later this week.

Next was getting up to Kaski. With the fuel shortages, this is more challenging than it’s been, as the bus is running infrequently. Not to worry! I caught the back of a motorcycle ride and then secured a taxi to the bottom of “the jungle path” that climbs straight up from the valley to the house. Forget the bus, man.

So first of all, at the beginning of this path you have to cross over the Gandaki river, which is usually dry at this time of year, but swells in the summer and fall. We used to wade through it, but a few years back it got this nice concrete bridge. So I’m crossing the bridge, and…it just stops in midair. The last half of the bridge is suddenly no longer there.

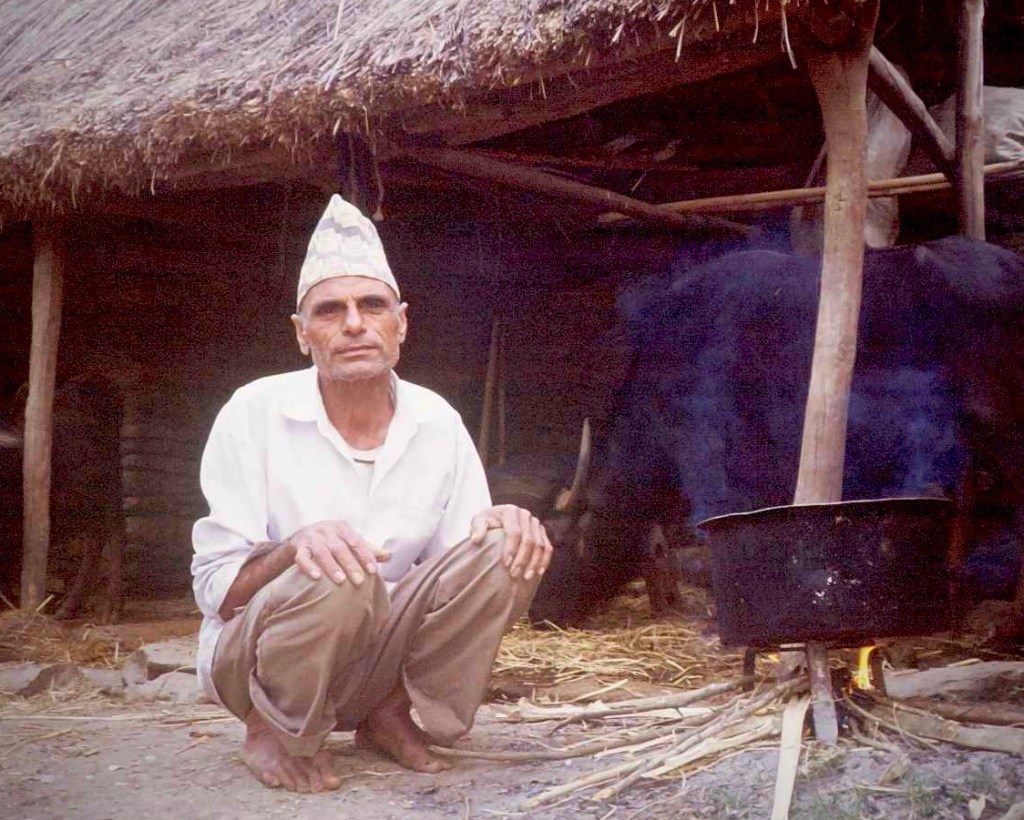

It takes me a few minutes to negotiate the drop over the ledge of the bridge with a torn ACL in my right knee that won’t let me jump down on to the rocky bed five or six feet below. I make my way over, progress to the bank a short way away, and there at the bottom of the path up to Kaskikot is this leathery guy resting next to a bundle of wood. He looks kind of resigned. I chat with him for a minute and then he asks for help lifting the bundle of wood.

“My son is really strong, he can carry this kind of load,” the man says woefully. “It’s just pretty heavy.”

Nevertheless, the bundle must be lifted, so we give it a try- fortunately I am more qualified than your average random American to hoist a bundle of wood on to someone’s back so it can be slung from their head and carried across a dry riverbed – but it is too heavy, he can’t get upright under the weight. He sets it back down, resumes his seat in the road, and looks resigned again.

“What’s with this bridge?” I ask. “Half of the bridge is missing.”

“I know!” He says. “The other night, I drank up a full belly and came here and fell right off of it.” He points to his forehead and says, “I got a bit of a bump right here.”

“I hear you,” I reply. “I’m not even drunk, and I nearly fell off the bridge too.”

“I hear you,” I reply. “I’m not even drunk, and I nearly fell off the bridge too.”

“Just went right over,” he recalls.

“Should we try this bundle of wood again?” I ask.

“Ok, but you have to come around the front and give me a hand.”

I heave the wood on to his back again and this time give him a hand to brace against as a counter balance, and he stands up.

“Thanks, bye,” he says, as if it makes sense that I appeared for this interaction. Off he goes.

Partway up the jungle path I run in to two kids coming down. They stop me.

“Where are you from?” they ask me in English.

“America. Where are you from?”

“Puranchaur,” the little boy answers.

“Oh, I’m going to Puranchaur on Tuesday,” I say. It’s one of the villages where we launched last year. I ask what grades they are in: four and eight. “So,” I say to the fourth grader, “do you brush your teeth at school?”

“Yep,” he answers.

“Huh. For about a year, right?”

“A little less than a year,” he says.

“Cool,” I answer, and down the path they go.

Finally I come out the top of the jungle path and emerge at the water tap in Kaskikot.

“LAURIEEEE!” the ladies cry. “Here you are, just in time for wood cutting to start tomorrow! Last year you came to cut wood, and this year you’re here to cut wood!”

YES. This is the gold medal of the Welcome Olympics. And yes, when I go to cut wood, I understand that it is a memorable experience for all of us.

On my way to the house, a few other people – completely independently – express their approval that I have arrived just in time for wood chopping. I am winning at Nepal.

At last, I drop over the spine of the ridge and there is home. Baby O’Neil is tethered outside, her wet nose pointed quizzically my way; she has grown some brown fur. The hillside is dotted with jubilant yellow mustard flowers. There is the familiar line of the Annapurnas rising in to the dusky sky, distant and close. No matter the path that brings me to this piece of land, it always appears the same way, luminous and inevitable.

*

And the truth is that if you landed here now, from anywhere, you’d be amazed to find that the apocalyptic situation that’s on the TV is not how things look. That’s because the collapsed buildings that the photographers zoomed in on aren’t the whole story. In fact, they were the tremor after the earthquake of poverty and poor governance, which is too chronic and undramatic to capture our attention, but remains most of the problem.

And the truth is that if you landed here now, from anywhere, you’d be amazed to find that the apocalyptic situation that’s on the TV is not how things look. That’s because the collapsed buildings that the photographers zoomed in on aren’t the whole story. In fact, they were the tremor after the earthquake of poverty and poor governance, which is too chronic and undramatic to capture our attention, but remains most of the problem.

There is no caution tape around Patan Durbar Square, or even around the base of this foundation that used to have a temple on it. The reconstruction is public and unbashful, but it’s also not desperate. In a courtyard tucked away to the left, bricks are patiently stacked up and a young couple is talking furtively under a tree.

There is no caution tape around Patan Durbar Square, or even around the base of this foundation that used to have a temple on it. The reconstruction is public and unbashful, but it’s also not desperate. In a courtyard tucked away to the left, bricks are patiently stacked up and a young couple is talking furtively under a tree.

sent me a disappointed email saying she’d never been able to get anything together to help Bishnu’s village. One organization after another had either refused to help, or said they’d help and then backed out.

sent me a disappointed email saying she’d never been able to get anything together to help Bishnu’s village. One organization after another had either refused to help, or said they’d help and then backed out.

We had a few special deliveries as well – cash relief for

We had a few special deliveries as well – cash relief for

sure why so many of the people in Banjang had made structures with such obvious problems. We decided we’ll do our best to provide day employment for some of the Sirwari people to come up and help the people in Banjang. We’ll see how that goes. In any case, at least these folks will be able to move out of the buffalo sheds and such. I will venture to say that if we had not required that people build before providing these roofing sheets, this is an area where a lot of our tin would likely have sat in the yard or been thrown on top of unsafe houses.

sure why so many of the people in Banjang had made structures with such obvious problems. We decided we’ll do our best to provide day employment for some of the Sirwari people to come up and help the people in Banjang. We’ll see how that goes. In any case, at least these folks will be able to move out of the buffalo sheds and such. I will venture to say that if we had not required that people build before providing these roofing sheets, this is an area where a lot of our tin would likely have sat in the yard or been thrown on top of unsafe houses.