For about two years now, we have been hard at work lobbing the new province government for health policy that includes primary oral health care. I’ve found myself hesitant to blog about many of the twists and turns in this aspect of our journey because political issues feel so sensitive while they are unfolding. And yet this phase of our adventure has produced some of the most colorful, absurd, harrowing and triumphant experiences we’ve ever experienced. Advocacy is, after all, a combination of showing up at government offices, making connections, making connections from connections, inviting people out to see our work, giving presentations, writing policy recommendations, rewriting policy recommendations, cajoling officials for meetings to discuss policy recommendations, and drinking tons and tons of tea and coffee over many coffee tables. These activities are exciting enough in a well-established, stable government. We are working with a government that is has been in perpetual transition for decades, with roads that wash out, with wise men and power saris, with astrological events that dictate the movements of both presidents and wedding parties.

I mean, all kinds of things happen. It is a shame not to tell you about some of them, some of the time.

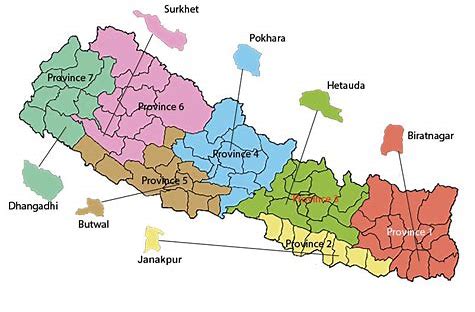

Recently, we had a breakthrough: Province #4, ours, re-established a previously defunct “Basic Oral Health Training” for primary care providers. We spent almost all of the summer of 2018 madly campaigning for this training. The five provinces of Nepal and the provincial government structure itself had at that time only recently been established – prior to 2017, the federal government was sub-divided by 75 districts – and it would still be some time before personnel had their job parameters defined in the new structure. But our efforts that summer eventually paid off, and recently, through a winding chain of events and people, writes and rewrites, submissions and resubmissions, and patience possible only thanks to some amount of beer, a province-level Basic Oral Health Training budget training descended from the heights of government.

The training is not actually designed yet, so it is fragile and easily gutted, but this also our first major policy breakthrough at a high level of government. It taught us a ton about collaboration, persistence, and the emerging structure of Nepal’s new decentralized governance structure. Even this small-big step would have been impossible to accomplish by working alone.

So this winter, our sights are trained on the Province Training Centre, where the official Basic Oral Health Training will be delivered. This training has a long history in Nepal that I will share at a later time; suffice to say that the essential focus of Jevaia over the last decade has been implementation of care after health care workers have taken Basic Oral Health training that’s provided outside our organization. So by nature, our role has involved a lot further training and refining of skills. If there’s one thing we’ve been up to our, um, teeth in (sorry it was too easy), it’s training and professional support for midlevel providers to do “basic oral health care” in Nepal’s primary care system. That’s why we exist, and it’s how all of our health post clinics and community programs survive against tremendous headwinds.

Now, as you can see this is all very serious business, and our recent meeting at the Province Training Centre rose to the gravity of the occasion. With this shiny, hopeful budget allocated, it is essential that we lobby for a training program that reflects what we’ve learned in over a decade of up-skilling midlevel providers to deliver rural oral health care. So we printed out materials. We reviewed key strategic points. We went to the Province training center.

“You guys!” Rajendra, our Medical Coordinator, cried as we crossed the threshold of the Province Training Centre, examining his feet with a mix of alarm and delight and curiosity that is unique in this world to Rajendra. “I’ve worn the office slippers!” He giggled, and then looked shocked, and then giggled again. Indeed, a brief review of Rajendra’s feet confirmed that he was in fact wearing a pair of the shower shoes we use inside our carpeted office, and his sneakers were still safely stowed on the shoe rack by the office door.

“You guys!” Rajendra, our Medical Coordinator, cried as we crossed the threshold of the Province Training Centre, examining his feet with a mix of alarm and delight and curiosity that is unique in this world to Rajendra. “I’ve worn the office slippers!” He giggled, and then looked shocked, and then giggled again. Indeed, a brief review of Rajendra’s feet confirmed that he was in fact wearing a pair of the shower shoes we use inside our carpeted office, and his sneakers were still safely stowed on the shoe rack by the office door.

I began to giggle too. “Maybe nobody will notice?” I said.

“Sita Ram sir!” Rajendra announced to our Program Director, excitedly. “I’m wearing the office slippers!” He couldn’t help it. He’ll agree with me when he reads this.

We were led in to the office of the government’s oral health Training Coordinator, where we left our shoes and shower slippers at the door, conspicuously not blending together.

We had a lengthy, complex, and sometimes coded meeting with the Training Coordinator. We were thrilled to find out that a technical working group is to be formed and we are invited to send a representative. The Training Coordinator requested that we also submit an evidence basis for our recommendations, and I will spend the next week compiling a selection of scientific literature around an “augmented Basic Package of Oral Care.” (For you nerds out there, the BPOC was developed with the support of the World Health Organization back around 2003 and is well documented in the literature; meaning we didn’t invent it, our business is to translate it in to practice in the face of real-world challenges.)

From the Training Centre, we re-donned our shower slippers and moved to the Health Division, the government department the Training Centre sits under. There, at the door, we ran in to none other than our past Jevaia program director! Nabaraj now works as a training coordinator in the province offices – perhaps a hopeful sign for us. We were warmly welcomed and led in to a cavernous office with an enormous with a desk at one end, and, per Standard Operating Procedure, tons of couches arranged against all free wall space. The couches were populated by a dozen or so visitors, people we didn’t know, who were both together and separately in an ambiguous state of meeting with the official we had come to see: The Health Directorate.

We took up arbitrary seats on couches where seats were available. This scattered Sita Ram far on a westward couch, while Rajendra, Rajendra’s shower slippers, and I secured side by side perches on an eastward couch. From there on out, in order for us to talk to Sita Ram, we had to either sign or speak very loudly over cross-talk from the northward visitors, who occupied the longest line of couches and either were or were not meeting with the Health Directorate, and may or may not have all been a single group with a unified agenda. There was no way to tell. Luckily, our former director Nabaraj was able to sit nearby me, on the adjacent westward couch, with only a fat faux-leather arm separating us, which made for good chatting and time to assess the situation.

We remained in this configuration for some time, until the room quieted and, based on a cue I could not identify, the Health Directorate affably invited us to introduce ourselves.

All of the people on all of the couches remained at their stations as we took the floor from our arbitrary seats among them.

Sita Ram went first, and then Rajendra. And then it fell to me to introduce myself and provide a general history and outline of our project, and why we were at the Health Division. In Nepali, with all the important couches watching.

The Health Directorate was gracious and curious. He asked us a series of astute questions about the need for primary oral health services in Nepal and about evidence and evaluation for our project model. He has a PhD in the sciences and absorbed our answers thoughtfully.

“You are here,” he said, “at the right time.”

We held our breaths. This was a good start.

Suddenly, the door opened and a group of men walked in.

All the heads on all the couches rotated toward the door.

“Namaskar, sir!” exclaimed a young, brisk man at the front of the group. The Health Directorate rose to meet them.

“We have brought you” –the young man held out a package, importantly– “a Christmas Cake!”

A murmur rippled across all of the couches of people. The Health Directorate reached out to receive a festive box. He thanked the men profusely. Without disrupting our key role as a riveted audience, I was able to lean over to Nabaraj and deduce that the men had come from a local hotel where the government hosts many of its meetings and gatherings.

“A Christmas Cake!” exclaimed the Health Directorate. “How wonderful!”

“How wonderful!” hummed the Couch Sea.

It was decided in short order to adjourn to the next room for Cristmas Cake. The entire room of people rose and passed through a door behind the Health Directorate’s desk, which led us in to a board room with a long, shiny table. The Health Directorate sat down at the head of the table; Rajendra, Sita Ram and I took seats all the way near the other end, and the as-yet-unidentified substantial company filled up the positions in between. The hoteliers huddled around the Health Directorate and bowed their heads over the Christmas Cake box, which was opened delicately to reveal a white iced fruit-cake with a neat candy-cane trim.

Paper plates were produced out of nowhere.

Paper plates were produced out of nowhere.

The Health Directorate began the careful process of dividing the roughly 6-inch cake in to precisely calibrated slices for the large room of attendees. Each offering was gravely placed upon a paper plate and passed to the right. Each person then continued passing the plate until it had circulated the long board table and ended up with the person sitting to the left of the Health Directorate. The Christmas Cake circulation continued thusly until all had been served. To the best of my knowledge, there was not a single Christian in the room, including me.

“What delicious Christmas Cake,” we cooed in turn.

Back at the office later, everyone wasted no time in celebrating the shower slippers for their trip to the Province Offices today. “How’d it go?” the rest of the team asked.

“Amazing,” we said. “We have no idea what happened.”

I sat down at my desk to begin compiling our package of research articles.

*

It has to be said that as I re-enter beautiful country that has welcomed me as a daughter without asking any questions, the borders of the U.S. are heavy on my heart. As always, I casually purchased my visa upon arrival in the Kathmandu airport. At our office, everyone wanted to know what on earth is going on in America. The papers say that New York is receiving many stranded children, including in Harlem just a stone’s throw from where I lived and taught art in schools for many years. I find myself thinking about the years I have

It has to be said that as I re-enter beautiful country that has welcomed me as a daughter without asking any questions, the borders of the U.S. are heavy on my heart. As always, I casually purchased my visa upon arrival in the Kathmandu airport. At our office, everyone wanted to know what on earth is going on in America. The papers say that New York is receiving many stranded children, including in Harlem just a stone’s throw from where I lived and taught art in schools for many years. I find myself thinking about the years I have

villagers can build anything out of anything. The overall approach being used with transitional housing is to provide a critical piece of hardware – THE ROOF – and let people build around it.

villagers can build anything out of anything. The overall approach being used with transitional housing is to provide a critical piece of hardware – THE ROOF – and let people build around it.

Lamjung district borders Kaski immediately to the East, and shares its other border with the district of Gorkha. The Lamjung/Gorkha border was the epicenter of the April 25 earthquake.

Lamjung district borders Kaski immediately to the East, and shares its other border with the district of Gorkha. The Lamjung/Gorkha border was the epicenter of the April 25 earthquake.